Understanding the Psychology of Misinformation: A Campus Talk

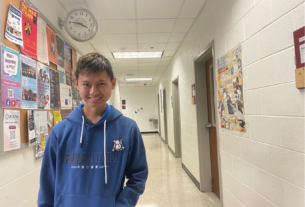

While they remain important components of the issue, the increasing abundance of misinformation cannot be entirely attributed to technology and interconnectedness. Without the individual and the combined actions of many, misinformation would remain confined to its source. On Oct. 27, employing the topics of the 2020 presidential election and recent increases in vaccine hesitancy, PVCC Associate Professors of Psychology Dr. Adam Johnson and Dr. Michael Rahilly sought to explain the role of human psychology in facilitating the spread of misinformation in a campus talk titled “The Psychology of Misinformation.”

The discussion was centered around measuring just how much of an effect human psychology had on facilitating the spread of misinformation, with the two professors making mention of cognitive biases, as well as identity and social influences, all while seeking support from a series of studies and the application of other psychological concepts. This effect was, as demonstrated by Johnson and Rahilly, vastly more than one would think.

Johnson began the talk. He accompanied explanations of authoritarian psychology and confirmation bias with the example of the 2020 presidential election and the many disputes surrounding its outcome. He credited Bob Altemeyer for his extensive work on the psychology of authoritarianism. The authoritarian personality was explained as someone with an unwavering adherence to a preferred authority, even to the point of justifying violence. He defined confirmation bias as an inclination of the individual to validate their beliefs with their preferred sources. These two factors were highlighted as causes of disputes to the 2020 presidential election results, with mention of studies conducted relating these concepts to the issue.

Johnson made a particularly interesting mention of social media as strengthening the effect of confirmation bias due to its incredible levels of personalization, something that will only increase as these platforms continue to develop.

Vaccination hesitancy was the focus of Rahilly’s portion of the talk, a topic that was a little more complex. Mention of confirmation biases reappeared in this portion of the talk, along with mentions of social identity and conformance biases as well. He identified personal and social identity as integral components of one’s sense of belonging. Consequently, they have a great deal of influence on human behavior. The conscious rejection of information could occur at the hands of an individual’s social identity and conformance biases, Rahilly stated.

From here, the complexity of this particular topic became more apparent. While concepts such as confirmation, social identity, and conformance biases could be easily explained and exemplified. It was the combination of these things with the unique conditions of the pandemic that caused such widespread vaccine hesitancy. Firstly, the stress of the pandemic accelerated the effects of these biases in influencing those resistant to vaccines. This stress was combated with what Rahilly described as fast thinking coping mechanisms. In this particular case, these mechanisms were the rejection of information in the interest of maintaining social belonging. The newness of the vaccine and a lack of education in science and the scientific process further contributed to the spread of misinformation and vaccine hesitancy, Rahilly added.

Both Johnson and Rahilly used the examples of the 2020 presidential election and vaccine hesitancy amid the pandemic to explain the effect that human psychology has on the spread of misinformation. Johnson’s brief discussion of the 2020 presidential election was accompanied by explanations of authoritarian psychology and confirmation bias. Rahilly’s portion of the talk related confirmation, social identity, and conformance biases to the incredibly unique nature of the pandemic.

It was, however, some of Johnson’s last statements in his portion of the talk that resonated most. “The internet and social media platforms have made it easy to select information sources that align with our views and opinions” read one of Johnson’s presentation slides, to which he added “…a stronger source of confirmation bias is going to come from the internet.” Social media platforms will only increase in personalization as data collection and analysis becomes more sophisticated. The heightening effects this will have on confirmation bias in the future are unthinkable.